Millstone Types: French Burr Stones

Made from silica-rich chert

AKA French Burrstone, Buhrstone, Buhr Stone, Bur Stone

Singleton Mills homepage > Overview of Stone types used for Millstones > French Burrstones

Widely prized for their milling qualities

Across the world, the millstone material that was almost always regarded as the best was a type of chert found in the Paris Basin in France. Millstones constructed from this material were called 'French Burr Stones'.

Above, an impressive French Burr Stone on display at M. Joseph Markey's beautiful Steenmeulen Windmill in France. Most French Burr Millstones that survive today have the distinctive segmented structure seen in this stone. The brownish coloured segments in the outer ring differ in hardness and porosity from the white inner segments – enabling the stone to mill flour more efficiently. The stone has numerous cavities in it, which are believed to assist with the grinding process. Photograph by Les Dollin.

French Burr millstones were prized because they could produce a very fine, white flour,A much in demand. In contrast, British Millstone Grit stones deposited gritty residues in the flour, and the imported German Cullin millstones produced a dark dust that discoloured the flour. So even though it was very expensive, French Burr Stone was imported into Britain for milling from at least the 1500s through to the 1800s.[1]

A: French Burr Stone flour. French Burr Stones could separate large flakes of wheat bran (outside layer) from the starchy endosperm. This made it easier to sieve the unwanted bran out of the meal, producing a whiter flour.[2]

The French Burr Stone quarries and workshops

French Burr Stone came from a large complex of quarries near La Ferté-sous-Jouarre and Épernon, in the vicinity of Paris in France. Whilst the earliest records have long disappeared, quarrying of this stone had begun by the 1400s. Over time, large workshops were established nearby, where workmen shaped and finished the cut stone.

Above, tradesmen dressing millstones in the Société Générale Meulière workshop at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, near Paris, France.

The La Ferté-sous-Jouarre millstone trade lasted until about 1940, when competition from the new roller mill technology for flour mills finally brought stone milling to an end. However, after 1945, 'Composition Millstones' B were produced there until the 1960s.[1]

B: La Ferté-sous-Jouarre Composition Stones. Presumably, these Composition Stones were the type of artificial millstones made from granulated French Burr Stone material.

French Burr Stone characteristics

French Burr Stone is a high-silica, light-coloured chert. This stone is very hard, and it often contains numerous holes that presumably improve its grinding qualities. These holes include minute fossils in the stone.

Above, detail of the smooth surface (very hard but almost waxy in appearance) of a French Burr Millstone. Two tiny round charophyte fossils (see red arrows) are embedded in the surface. (Dr Joseph Hannibal kindly verified the identity of these fossils for us. Read more about Dr Hannibal's reasearch on these fossils, below.) A larger cavity in the stone can also be seen at the centre of this image. The full width of this image shows a 20mm-wide section of the stone. This French Burr Stone is on display at Rockley Mill Museum, NSW. Macro image by Anne Dollin.

Dr Joseph Hannibal of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, USA, a geologist with a special interest in millstones and their fossils, kindly provided the following additional information:

– The stone from the quarries at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre is chert, a sedimentary rock in which silica has replaced original calcium carbonate in limestone.

– Sometimes French Burr Stone (or Buhrstone) has been described as 'quartzite', but this is incorrect. Real quartzite, a metamorphic rock, has been used to make millstones with some success in USA, but the French stone is a sedimentary chert.[3]

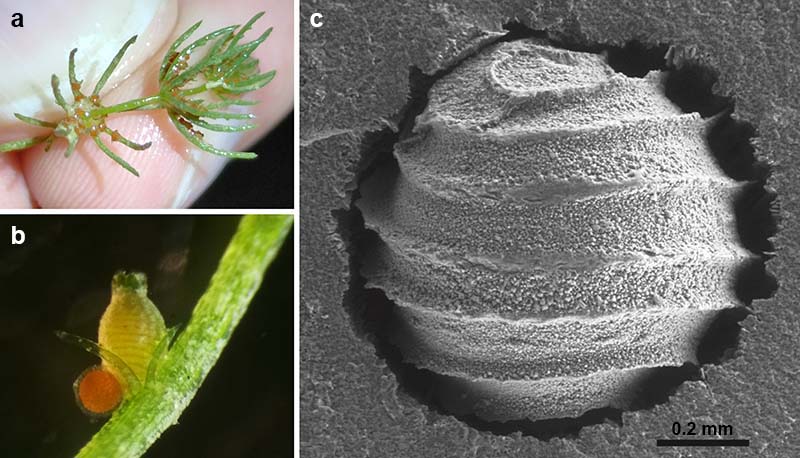

– French Burr Stone contains small fossils of charophytes and gastropods. Charophytes are freshwater green algae. The charophyte fossils found in French Burr Stone are tiny spherical structures from the algae used in reproduction (gyrogonites) – see photographs, below. There are also fossils of pieces of the stems and branches. Not all French Burr Stones have these distinctive fossils, but some have them in large numbers.[4]

Above, images of charophyte algae:

• a – b, the modern-day charophyte species, Chara globularis; a, tiny stems and branches of C. globularis, with orange-brown reproductive structures, are held in a person's fingertips; b, a magnified view of the male (left) and female (right) reproductive structures of C. globularis. The female structure has distinctive parallel bands. Images from iNaturalist website, CC BY-NC. Photographs by: a, Victor Hoyeau in France; b, Thomas Nogatz in Germany.

• c, a fossil from an extinct species of charophyte alga (Gyrogona medicaginula) embedded in a French Burr Stone. This is one of the female reproductive structures of this extinct species, and it also has distinctive parallel bands which spiral around its surface. Scanning Electron Microscope image from a scientific paper by Joseph Hannibal. [5] CC BY-NC.

– Gyrogona medicaginula charophyte fossils clearly characterise French Burr Stone. They are each about 1 mm wide and can usually be seen with a hand lens. French Burr Stones were exported to many countries around the world, especially in the 1800s. By looking for these fossils in the stone, it is possible to identify millstones which were quarried in the Paris Basin.

– French Burr Stone has tiny cavities in it, including those contributed by the fossils. These cavities added to the desirable qualities of these millstones – they were thought to provide sharp cutting edges, that may help grind the wheat.[4]

New research on Australian French Burr Stones ... and their amazing 30 million year old fossils! |

Monolith vs Composite French Burr Stones

Monolith stones.

Full-sized monolith millstones, cut in one piece, were initially produced in the La Ferté-sous-Jouarre quarries. However, a shortage of sufficiently large blocks in the quarries, difficulties in transporting the heavy stones, and technological advancements in millstone design led to a decline in the production of monoliths by the mid 1800s.[1]

Composite stones.

An alternative system was established where smaller blocks of the Burr Stone material were prepared in the quarries for the export market. Then in Britain, USA, and elsewhere, workshops cut these blocks into wedges and assembled them into complete 'composite' millstones.C [6]

C: Composite Stones. This system of millstone manufacture allowed more advanced millstone designs to be used. For example, millstones with better milling properties could be made by placing softer stone segments near the middle of the stone, and harder segments near the outside edge. Moreover, some millstone manufacturers in Scotland used a cheaper British stone for the middle section of their 'composite' French Burr Stones, to reduce the overall millstone cost.[1, 7]

Above, the wedges of stone in one of the French Burr Stones, on display at Rockley Mill Museum, have begun to separate. This interesting exhibit shows how the stone wedges were so precisely cut by the manufacturer to fit together like a jig saw puzzle. Rockley Mill Museum, near Bathurst, NSW, has three full-sized millstones on display, as well as a steam engine and a fascinating collection of flour milling machinery. Image by Anne Dollin, 2024.

In 1944, a description of how the composite stones were constructed was given in a paper read at the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, London:

'The small blocks are shaped rather in the manner of stones for an arch and are cemented together with plaster of Paris, which wears equally with the stone, to form a round stone, bound round the edge with hoop iron; the working face is dressed level and the back, which has been left irregular, is smoothed off with plaster of Paris. Frequently a cast iron ring bearing the maker's name and the year of manufacture is let into the plaster round the eye of the runner stone.' [8]

The size of the French Burr Stone trade

By the end of the 1700s, substantial quantities of the smaller Burr Stone blocks were being imported into Britain. This trade even continued during periods of warfare between Britain and France, and at least for a short period in 1809, a special licence was granted to import Burr Stone during the Continental Blockade.[6]

Perhaps 30,000 - 40,000 pairs of French Burr Stones were in use in Britain by the 1850s; and 3,000 - 4,000 pairs may have been manufactured in Britain annually.[9]

In Britain, most mills had at least one pair of French Burr Stones. Sometimes mixed pairs were used, such using as a French Burr Stone runner stone (the upper stone) with a Welsh bedstone (the lower stone). A pair of cheaper Millstone Grit stones might be used for general milling.[2] Although very costly to import, a pair of French Burr Stones could last for a generation or even a lifetime. French Burr Stone was hard and extremely difficult to dress, but the surface wore very slowly and needed re-dressing less often.[1]

Above, a French Burr Millstone set up as a Bed Stone in the Acorn Bank Watermill in Cumbria, England. This photograph was taken in 2022 just before this stone, still being actively used by the watermill, was taken out so that the dressing pattern could be re-applied. Photograph courtesy of Martin Fagan and the Trustees for Acorn Bank Watermill.

Could local stones match French Burr Stones?

The high price of French Burr Stones and problems with obtaining imported stones prompted campaigns to find local alternatives 'as good as French Burr' in Britain, Australia and elsewhere.

– In Britain in 1798, a London Society announced a major prize for the discovery of stone in Great Britain 'equal in all respects to that stone known by the name of French Burr'. Applicants sent in claims from Scotland and Wales.[10]

– In the eastern United States of America in the early to mid 1800s, chert millstones, similar to French Burr Stones, were quarried at more than 20 locations.[11]

– Then in Australia in the mid 1800s, a number of 'Colonial Millstone' varieties were announced with great fanfare in the local newspapers.

Unfortunately, none of these alternative millstones lived up to their discoverers' high hopes, and these enterprises were almost entirely short lived.

In the end, it appears that the French Burr Stones of the Paris Basin were unsurpassed in their exceptional flour-milling qualities.

REFERENCES

1. Ward, Owen (1993) French millstones. Notes on the millstone industry at La Ferté-sous Jouarre. The International Molinological Society, Bibliotheca Molinologica, 11: 1-75.

2. From Quern to Computer. Mills Archive Trust.

3. Dr Joseph Hannibal, personal communication, 2024.

4. Hannibal, Joseph T, Reser, NA, Yeakley, JA, Kalka, TA and Fusco, V (2014) Determining provenance of local and imported chert millstones using fossils (especially Charophyta, Fusulinina, and Brachiopoda): examples from Ohio, U.S.A. Palaios, 28:739-754.

5. Hannibal, Joseph T (2019) Widespread North American occurence of millstones made of imported French chert (French buhr) containing charophytes. In: Anderson, TJ and Alonso, N (eds), Tilting at Mills: The Archaeology and Geology of Mills and Milling. Revista d’Arqueologia de Ponent extra 4, 283-293.

6. Jobey, George (1986) Millstones and millstone quarries in Northumberland. Archaeologia Aeliana, 5(XIV): 49-80, page 51.

7. Tucker, D Gordon (1982) Millstones north and south of the Scottish border. Industrial Archaeology Review, VI(3): 186-193.

8. Russell, John (1943) Millstones in wind and water mills. Transactions of the Newcomen Society, 24(1): 55-64.

9. Tucker, DG (1977) Millstones, quarries, and millstone-makers. Post-Medieval Archaeology, 11: 1-21, pages 10 and 12.

10. Ward, Owen (1985) British Burrstones, 1799-1821. Melin, 1: 31-45.

11. Hockensmith, Charles D (2019) American millstones similar to the French burr: 19th-century attempts to find substitutes. In: Anderson, TJ and Alonso, N (eds), Tilting at Mills: The Archaeology and Geology of Mills and Milling. Revista d’Arqueologia de Ponent extra 4, 257-281.

Read More About Millstones

•• Overview •• Basalt-like Cullin Stones •• Millstone Grit •• Old Red Sandstone, Puddingstone, and Lodswoth Stone •• Granite •• Limestone •• Artificial Millstones •• Norfolk Island Millstones •• Colonial Millstones ••