The Fat-Tailed Sheep on the First Fleet

Australia's first sheep

Cape Fat-tailed sheep, broad-tailed sheep, Afrikaner sheep, Cape Town, Cape of Good Hope, Africa

Singleton Mills homepage > The first sheep in Australia

The sheep on the First Fleet

Captain Arthur Phillip and the First Fleet spent about a month at Cape Town, a port in southern Africa, on their way to Australia in 1787. There Phillip purchased about 500 live animals for the new penal colony they were to establish at Sydney Cove.[1]

Amongst these animals were at least 29 sheep. These animals would become the first sheep to be landed on Australian soil.

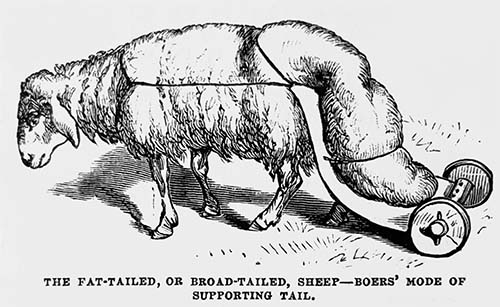

Above, a drawing of the Fat-Tailed Sheep breed from South Africa, that was taken to Australia on the First Fleet in 1788. Source: Locher (1881) article – see below.

Cape Fat-Tailed Sheep

These sheep were known as Cape Fat-Tailed Sheep. Their coats were less woolly than modern Australian sheep – they were bred mainly for their meat, not their fleece.

A remarkable feature of these sheep, that looks very strange to Australian eyes today, was their enormous, fat tails. Arthur Bowles Smyth commented on the tails of these sheep in the journal he kept during the First Fleet.[2] When the sheep were well fed, their tails would pack on huge quantities of a flavoursome fat that was considered a delicacy in southern Africa.

A fascinating and detailed description of the Fat-Tailed Sheep appeared in an 1881 magazine article. It is of such interest, that we reproduce it here, almost in full. Fat-Tailed Sheep are still bred in many parts of the world, and this was the very first sheep breed imported into Australia.

The Fat-Tailed, or Broad-Tailed, Sheep.

Original Sketch of Travel, by August Locher.

Published in Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, May 1881.[3]

'One of the most remarkable of domestic animals, yet the one least known to civilized people, is unquestionably the fat-tailed, or broad-tailed, sheep, originally a native of Central Asia, but now found in various parts of China, India, North and South Africa. In the region last mentioned it was formerly particularly abundant, having, in fact, been, up to the time of that country's colonization by the English, the only species of sheep known there.

Somewhat inferior in size to the common sheep of Europe and America, it differs from the latter also perceptibly in shape, being narrower in proportion across the chest, wider across the hindquarters, and standing comparatively higher on the forequarters or shoulders, and lower on the hindquarters or haunches.

Its ears, too, are larger and more pendulous, and the ridge of the nose has a bolder curve. But by far the most striking characteristic of the subject of my sketch is its wonderful tail. Nature, for some inscrutable reason, has seen fit to encumber this gentle, timid little animal with a tail far bulkier and heavier than that of any other quadruped now living – a caudal appendage simply preposterous in its weight, shape and dimensions, considering the size and strength of the animal.

Exaggerated though the statement may appear, it is nevertheless scrupulously true that the tail of a healthy, full-grown sheep of this species seldom or never weighs less than twenty-five pounds, while specimens with tails of forty, fifty and sixty pounds in weight are not rare – nay, the tails of some exceptionally large and fat animals have been known to reach the almost fabulous weight of seventy, seventy-five, and even eighty pounds, an avoirdupois considerably in excess of the weight of all the rest of the animal itself.

Though admittedly almost beyond belief, this assertion will readily be confirmed by any South African sheep-farmer who has ever raised this species of sheep, and the writer is satisfied that live specimens, with caudals of the extreme weight mentioned, could be found in South Africa even now, though this class of sheep is no longer raised to any extent by the colonists, but only found in herds among the natives.

As may readily be imagined, the monstrous size and weight of the tail, hanging down inert and powerless over the hindlegs of the animal, greatly impedes its locomotion, and compels it to move only with a slow, ungainly, shuffling gait, downright painful to behold.

Luckily for this all but utterly helpless being, Dame Nature, as if to partially compensate it for this caudal affliction, has, as above stated, endowed the animal with forelegs perceptibly longer, and shoulders higher in proportion than other breeds of sheep, whereby the pressure of the ponderous tail upon the hindlegs is somewhat relieved; otherwise locomotion, particularly down-hill, would be all but utterly impossible to full-grown, fat and healthy animals, whose caudals have been known to attain a length of thirty-two inches, a width of twenty inches, and a thickness of fifteen inches.

That these prodigious tails are not mere monstrosities, but normal attributes of this peculiar breed of sheep, is clearly demonstrated by the lambs, which are invariably born with tails already slightly baggy in shape, distinctly indicative of that tendency toward extraordinary expansion.

The most remarkable feature of this caudal appendage, however, is its intense sensibility. The thermometer cannot be more sensitive to heat and cold than this tail is to the bodily condition of the animal; for no sooner does the sheep begin to suffer from any cause whatsoever, be it from disease, ill-treatment, hunger or thirst, than the tail forthwith commences to show it by decreasing in size and weight; but as soon us these causes of physical discomfort are removed it improves again in the same ratio as the health of the animal.

The tail of the healthy adult sheep has somewhat the shape of that of the beaver, and is entirely destitute of wool on the lower side, ie., the side facing toward the animal. It is broadest and thickest about ten inches from the apex or tail-end, and consists of the caudal vertebra, sparsely lined with fleshy muscles, and surrounded by huge masses of spongy fat and fatty tissue, permeated by innumerable nerves and veins, all radiating from the vertebrae, and rendering the ponderous tail, in spite of its clumsiness, a most sensitive part of the body.

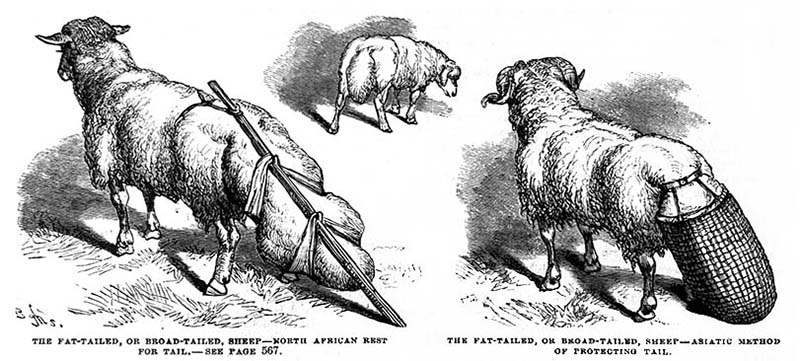

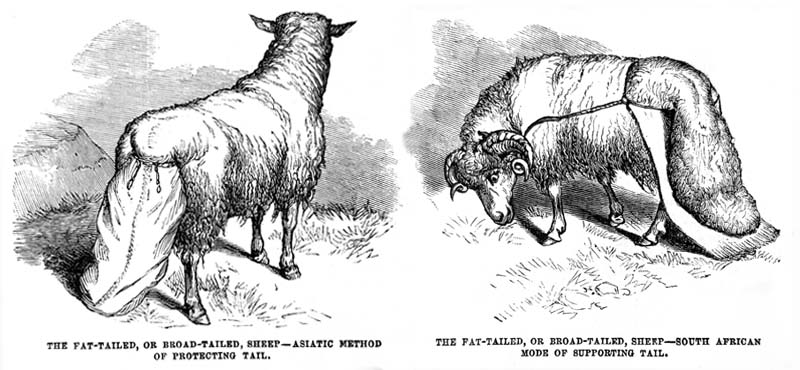

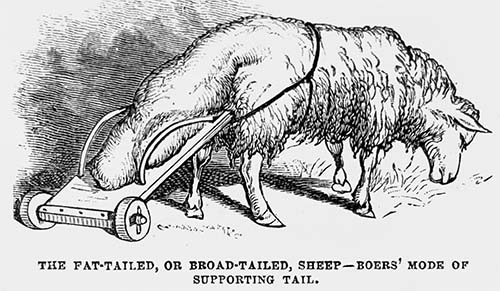

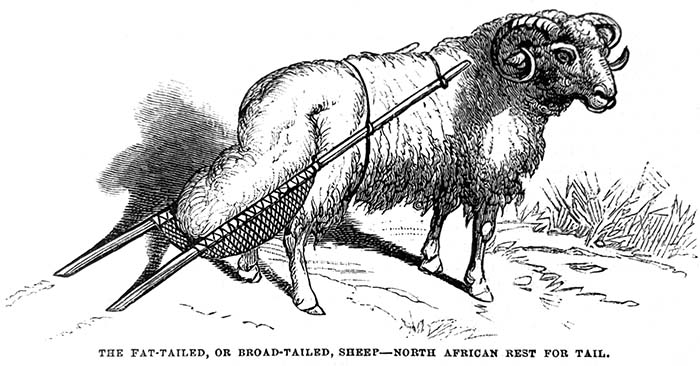

For this reason it is customary among people who raise this class of sheep to carefully guard heavy tails against injury from chafing on the ground, from laceration by sharp stones, thorns, etc., by means of various devices.

In Asia, bags of rawhide, felt, matting or other strong material, even wicker-baskets, are strapped over the heaviest tails. In North Africa, a stick about the size of a broomstick is so attached to the sheep as to rest with the one end on the hindquarters of the animal, while the other end is left to drag on the ground, and to this slanting stick the tail is suspended by means of bandages.

Some use two sticks, one fastened to the right, the other to the left, side of the sheep. Both sticks are left trailing on the ground, and on a piece of matting stretched between the two sticks immediately behind the animal, the tail is deposited.

Among the Bechuanas, Namaquas, and other Hottentot tribes of South Africa, the writer saw a still more simple contrivance used for this purpose. A piece of rawhide of sufficient length and width is passed apron-like under the tail, and left trailing on the ground, with the tail resting upon it. The Boers (Dutch-African farmers and stock-raisers) of the interior of South Africa also use the raw-hide apron for this purpose, or a piece of thin plank or board of suitable size, but they usually attach small wooden wheels to the lower or trailing end thereof, as shown in the accompanying illustration.

These various contrivances are, of course, only used on sheep whose tails have become too large and cumbrous to be carried without artificial support.

The fat of these tails is considered a delicacy, and used as butter in the countries where this species of sheep is raised. When fresh, it tastes sweet and pleasant-indeed, very much like good butter, which it resembles also in color.

The flesh of the animal, however, is decidedly inferior to our mutton, probably on account of its chronic leanness, for, strange to say, no amount of good feeding of the animal can induce the fat to settle on any other part of this sheep than upon its tail….

The wool of this species of sheep is soft, but shorter than that of most other domestic breeds, and consequently of inferior commercial value. Principally on account of this fact, the early English and Scotch colonists of South Africa gradually tired of raising the fat, or broad-tailed, sheep, and began importing English sheep of the Dorset, Ryeland, Cheviot, Leicester and other celebrated breeds, some of which throve well in the South African climate, while others did not acclimate themselves so readily.

Through crossing the different breeds with each other, they succeeded, however, in obtaining a breed adapted to the climate as well as profitable, and immense herds of this class of sheep are now met with all over South Africa, from the Cape of Good Hope to the banks of the Gariep or Orange River.

Within the last twenty years, enterprising colonists, in order to still further improve the wool of their flock, have imported a large number of the far-famed Merino sheep, mostly rams, which they allow to run among their herds.

As for the unfortunate subject of my sketch, it has long since been discarded by the speculative colonist, except as a sort of curiosity or memento of bygone days, still kept around the house, and is now only met with in considerable numbers among the Boers and Hottentots of the west coast and the far interior of South Africa.

Although undeniably a most interesting animal, all but totally unknown to the majority of civilized people, it is, strange to say, nowhere to be seen, to my knowledge, either in this country or Europe, not even in zoological gardens and menageries —for what reason I am at a loss to say, because it cannot be more difficult to acclimate than many other animals, indigenous to the same regions, which are exhibited ad nauseam throughout the civilized world.'

Later cross-breeding produced Australia's livestock today

Eric Rolls[4] wrote a very informative and readable account of the different breeds of cattle, sheep, horses, and pigs that were brought to Australia on the First Fleet. He then described the other breeds that were later imported, and how these animals were crossbred to produce the livestock breeds that Australia has today. Of course, important amongst these were the first Merino sheep that were brought to Australia, and established Australia's wool industry.

REFERENCES

1. Phillip, Arthur (1789) The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay. John Stockdale, London. Project Gutenberg.

2. Smyth, Arthur Bowles (1789) A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China. Edited by Colin Choat in 2020. Project Gutenberg Australia. Smyth wrote, 'Captain Sever laid in a plentiful stock at the Cape, notwithstanding the dearness of them, viz. sheep, remarkable for the enormous size of their tails'.

3. Locher, Arthur (1881) The Fat-Tailed, or Broad-Tailed, Sheep. Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, Vol 11(5), 567-570. Accessed via Internet Archive, May 2025.

4. Rolls, Eric (1984) A million wild acres. Chapter 1. Penguin Books. Australia.

Read About Sydney's First Flour Mills

•• Sydney's First Mill Builders •• Sydney's First Millstones •• Australia's Colonial Millstones ••