First Flour Mills in Sydney and Parramatta

1788 to 1810

Researched by Anne and Les Dollin

Singleton Mills homepage > The earliest flour mills of Sydney, NSW

Desperate food shortages of the early colonists

The First Fleet landed in Australia in January 1788 with over 1400 convicts, free settlers, marines, sailors, and other personnel. Governor Arthur Phillip was faced with the immense task of setting up a British penal colony at Sydney, New South Wales (NSW).

Above, the First Fleet in Sydney Cove in January 1788. Painting by John Allcot, National Library of Australia.

The new settlement was extremely isolated from support. The settlers had just travelled 24,000 km and an eight-month voyage from England, and they had little hope of receiving regular supplies of food by ship.

One of the first priorities for Phillip was securing a food supply for the settlement. The First Fleet had brought cargos of flour, salt meat, seed for crops, and some livestock. However, Sydney Cove had much poorer soil and less fresh water, than the settlers had expected. Their early crops failed.

Supplies soon ran low. In October 1788, Phillip had to send the ship, Sirius, on a seven month voyage to The Cape of Good Hope and back, to obtain more stores. The settlers endured rationing of food, and by April 1790, the colony faced the prospect of starvation.[1]

The difficulties of milling wheat by hand

For these British settlers, flour and bread were staple foods. However, wheaten flour was particularly difficult to produce within the colony. Even if wheat could be successfully grown in Sydney, the wheat grains, which are extremely hard, still had to be milled into flour.

Forty iron (or 'steel') hand-mills had been sent to Sydney with the First Fleet, but these needed to grind flour for 1400 people! Furthermore, the mills were poor quality, and gave many problems.[2] Unsurprisingly, the hand-mills soon wore out.

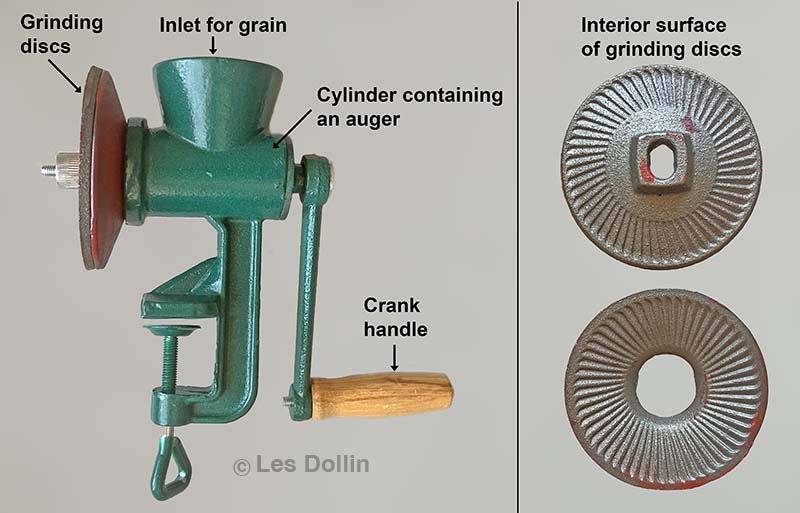

Above, this modern replica of a simple steel hand-mill for grinding grain provides an idea of the possible design of Sydney's first hand mills. We have not found any images of the original hand-mills that were used in Sydney in the early 1800s, although hundreds must have been imported or produced locally. We would be interested to hear from any reader who can provide such an image – please help us continue to expand the information about Australia's first flour milling enterprises on this website!

Milling grain with an iron hand-mill was also extremely labour intensive, and it required long hours of work to produce a supply of flour. About a quarter of a bushel A of grain per hour could be ground by a steel or iron hand-mill which was in good condition. However, if the mill was old or rusty, it could take took six hours to grind that same amount.[3]

A: Bushel. One imperial bushel of wheat weighs about 25 kg.

Additional difficulties faced the settlers when they tried to sharpen their hand-mills:

'… these mills were sometimes called steel mills, as the cutting parts… were hardened by a process of partial steeling known as "case-hardening." When such mills became worn by use, … it was necessary to first make them red hot and soften the iron, when they could be recut and again hardened for use.

This work was a trade in itself, but no steel-mill man was sent out in the First Fleet to do the work. Some considerable time afterwards a blacksmith was found who agreed to make these mills at five pounds each, and in later days, their manufacture and repair became a regular business in the colony.' [4]

Clearly the colony of Sydney, NSW, urgently needed to build some large-scale, flour mills. To the frustration of the Governors, nearly ten years would pass before the colony managed to build a reliable, powered, flour mill (such as those shown below). The First Fleet had brought some millstones to Sydney in 1788, but nobody knew how to build a mechanised flour mill.

Above, this large-scale flour mill, built in Parramatta, NSW, 40 years after the First Fleet, was a combination of a windmill (left) and a tidal watermill (right). Painting by George Wickham, 1849, State Library of NSW.

Sydney's first large-scale flour mills, 1792–1799

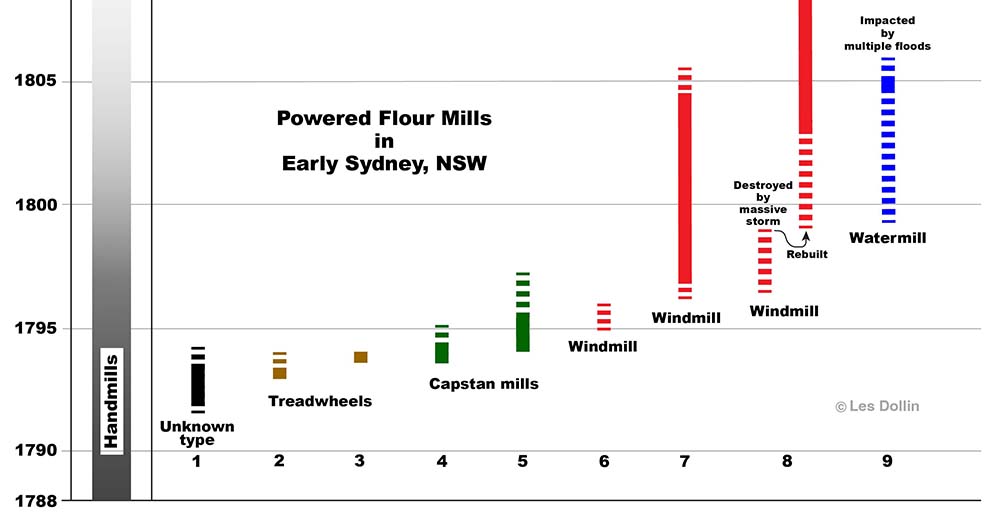

Nine attempts were made to construct powered mills in Sydney up until 1799. Only two of these mills had long-term success. Handmills continued to be used, until powered mills finally went into full production:

Above, a chart giving an overview of the nine flour mills that were begun in Sydney before 1800. Further details about each mill design can be found below. Small steel hand-mills continued to be used to grind flour by the settlers, from the beginning of the colony in 1788 until successful full-scale powered mills were finally constructed.

KEY TO CHART – click on the links below for more information.

NUMBER 1. Sydney's first powered mill.

NUMBER 2. Wilkinson's first treadmill design.

NUMBER 3. Wilkinson's second treadmill design.

NUMBER 4. Baughan's first capstan mill.

NUMBER 5. Baughan's second capstan mill.

NUMBER 6. An attempted windmill near Parramatta.

NUMBER 7. Sydney's first successful windmill built by Davis at Sydney Cove.

NUMBER 8. The Military Windmill at Sydney Cove. This mill was demolished by a storm in 1799 and construction had to begin again.

NUMBER 9. A watermill at Parramatta that was repeatedly impacted by river floods.

NUMBER 1: Sydney's first powered flour mill

This was a large mill[5] with a basic design at Parramatta (25 km west of Sydney). It may have already existed when Thomas Allen, a Master-Miller sent out by England, arrived in Sydney in 1792.[6] Allen was assigned to manage the Parramatta mill, and the Master-Millwright, James Thorp, who arrived in 1793, was sent to work with Allen.[7]

This mill only produced 'coarsely ground' wheat.[8] This is the kind of meal that would be produced if the miller tried to reduce the power needed to grind the grain, by increasing the gap between the two grinding stones.

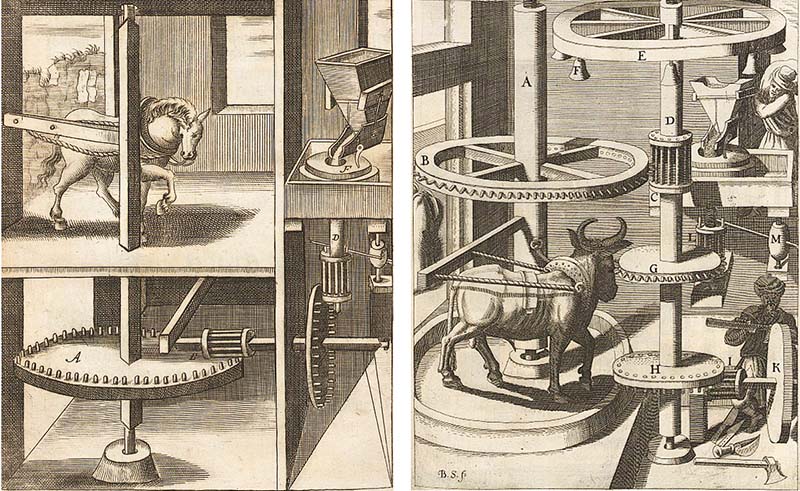

We have not yet found any original document recording the power source used by this 1792 flour mill. Norman Selfe's account in 1900 merely describes it as 'a building used as a mill.' [9] Although draught animals were scarce in Sydney at that time,[10] an important mill like this might have been allocated some horses or oxen to drive it. Alternatively, convicts may have powered it through some type of treadmill, or it might have been a primitive watermill.

Above, drawings showing two simple flour mills, dated 1661–1688: left, a mill driven by a horse, and right, a mill driven by an ox. In each case, a set of simple gear wheels transmits the power produced by the animal to a set of two grinding millstones (shown in the upper right of each drawing). Wheat is being poured into the centre of the pairs of millstones and ground flour is collected in the boxes around the millstones. One possibility is that the 1792 flour mill at Parramatta might have been powered by an animal using workings such as these. Both drawings are 17th Century scientific illustrations from Deutsche Fotothek.

Serious problems for this mill were caused by the unseasoned local timber that was used to make its gear wheels:

'This mill, from the brittleness of the timber with which it was constructed, was found to be unequal to the consumption of the settlements. The cogs frequently broke, and hence it was not of any very great utility.' [11]

Note: The above 1792 mill at Parramatta seems to be the earliest large-scale flour mill built in the Australian region. However, Nathaniel Lucas' 1796 watermill on Norfolk Island was the first powered flour mill that reliably worked.

NATHANIEL LUCAS In 1788, an outpost of the British penal colony was established on Norfolk Island, 1600 km northeast of Sydney. Emancipist, Nathaniel Lucas, built three successful large-scale flour mills there in the 1790s, and became a skilled millwright. Norfolk Island's unique Calcarenite Limestone Millstones were used in Lucas' flour mills. Lucas brought some of these Norfolk Island millstones to Sydney, NSW, in 1805, and built a series of successful windmills in Sydney (more details below). |

NUMBERS 2 to 5: Four Convict-Powered Mills

The next four flour mills that were built in Sydney, NSW, were powered by convicts.

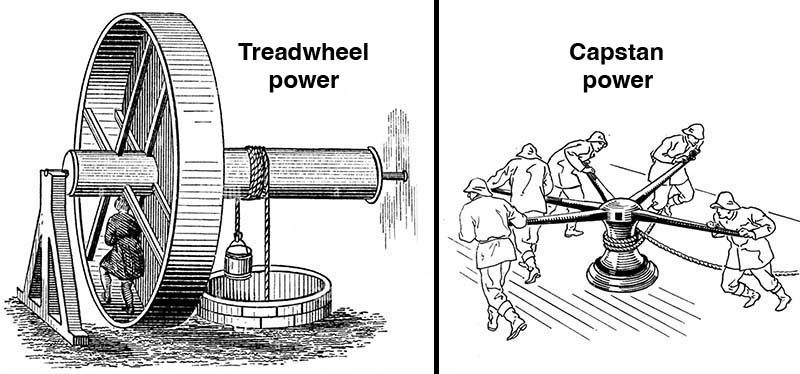

In 1793-1794, a convict named James Wilkinson made two attempts to build a mill, each powered by a treadwheel – as illustrated below left.

– The first was a two-man design with a 15-foot wheel driving the millstones – while the wheel did one revolution, the millstones did 20 revolutions; and

– the second was a six-man design with a 22-foot wheel.

Although Lieutenant-Governor Grose was impressed with Wilkinson's work, unfortunately neither of these designs was successful. In the first mill, the cog wheels, made from unseasoned local timber, rapidly failed; and in the second mill, the gearing was too complex, and it constantly broke down.[12]

Above left, a person operating a treadwheel to draw water from a well. This was the mechanism used in Wilinson's mills (see above);

Above right, men pushing capstan bars to pull up a rope on a ship. This was the mechanism used in Baughan's mills (see below).

In Sydney's four convict-driven mills, these power sources would have been connected to a pair of millstones via a set of gear wheels. The power produced by the treadwheel, or the capstan, would have driven the rotation of the upper millstone and ground the grain. Image sources: left, Thomas Ewbank (1849) A descriptive and historical account of hydraulic and other machines for raising water, ancient and modern. Internet Archive; right, Pearson Scott Foresman archives, Wikimedia Commons.

In 1794, in competition with Wilkinson, an emancipist called John Baughan (also known as John Buffin or John Bingham) designed and built a different kind of convict-powered mill. In Baughan's design, nine convicts powered the mill by pushing capstan bars around in a circle – as illustrated above right.

Baughan's design was decreed to be the best. So, he was commissioned to dismantle Wilkinson's mill and build a second capstan mill using his own design.[13]

It is not known how long Baughan's convict-powered capstan mills were kept in use, but they were, in time, to be superseded by wind-powered flour mills.

Valuable help from the new Governor

Meanwhile, back in England in 1794, John Hunter had been appointed as the next Governor of NSW. Hunter knew that the Sydney colonists were having major problems trying to build a flour mill. If he could bring some detailed plans and a set of mill components from England, he thought, this would greatly improve his chances of erecting a successful windmill in Sydney.

So, before Governor Hunter sailed to Sydney in 1795, he purchased a model of a windmill and some crucial internal mill components from Nathaniel Stedman of the Chatham area in England.

The windmill model was quite large. It was to be built on a '2-inch scale' and would pack in a 2.3m x 1.2m case.[14]

The mill workings Hunter requested were:

– 'Four wheels,

– One shaft of wood,

– One brake to stop, and

– some ironwork.' [15]

NUMBER 6: An attempted windmill at Parramatta

When Hunter arrived in Sydney in 1795, James Thorpe, the Master-Millwright, was given the job of erecting a windmill at Parramatta, using the windmill equipment that Hunter had brought from England.[16]

It appears that this mill was never finished, and the mill components may have later been used in one of the Sydney windmills.

NUMBER 7: The Ingenious Irishman's windmill

The first successful windmill to be built in Sydney was finally constructed by a convict who was not named in the official records. Despite this man's major achievement, Hunter simply described him as, 'an ingenious Irish convict'. [17]

This man was, in fact, John Davis, a convict who had arrived in Sydney in 1796 on board the Marquis Cornwallis.[18] Read the fascinating, but little-known, life story of the Ingenious Irishman, John Davis.

Davis' windmill was the first Government Mill to be built in the Sydney Cove area. It was located near today's Observatory Hill, west of Sydney Cove, in a place known some years later as 'Fort Phillip' or 'Flagstaff Hill'. The mill was completed in 1797 and had a small stone tower.

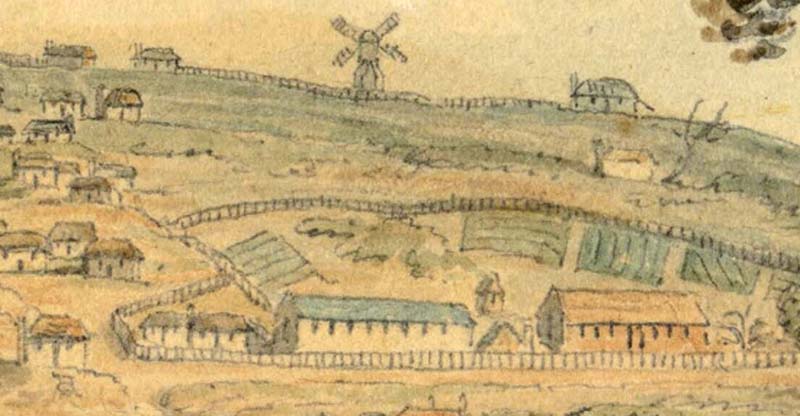

Above, a rare early painting of Sydney's first successful windmill – the first Government Mill, built by John Davis near Sydney Cove. Detail from a watercolour painting by Edward Dayes, 'Western view of Sydney Cove, 1797', National Library of Australia.

Three events, that impacted this windmill, illustrate the massive challenges faced by the mill builders in early Sydney:

– In March 1797, much to the disgust of Hunter, a thief stole part of the sail cloth that covered the wind vanes, bringing the mill to a standstill.[19]

– In April 1797, a heavy squall of wind made the wind vanes spin violently. This in turn, made the millstones turn so fast that one broke into pieces. According to Collins 1798, a millstone fragment 'so severely wounded Davis the millwright in the head that his life was despaired of.' [20]

Davis survived but was severely disabled by this accident.[21] Despite this tragic accident, carpenters got the mill running again within a few days.

– Finally, in July 1797, another gale of wind tore off two of the vanes of this mill.[22]

Despite these calamities, Hunter was well pleased with the millwrighting work of John Davis, his 'ingenious' Irishman. Hunter wrote:

'… we have finished a wind mill at Sydney since November last, with a strong stone tower, it is the first ever erected in this country and will last long, it is now at work, it was begun and finished under all our difficultys in less than five months…' [23]

The mill continued to operate until about 1805, although its foundations subsided due to the poor-quality mortar used in its construction.[24]

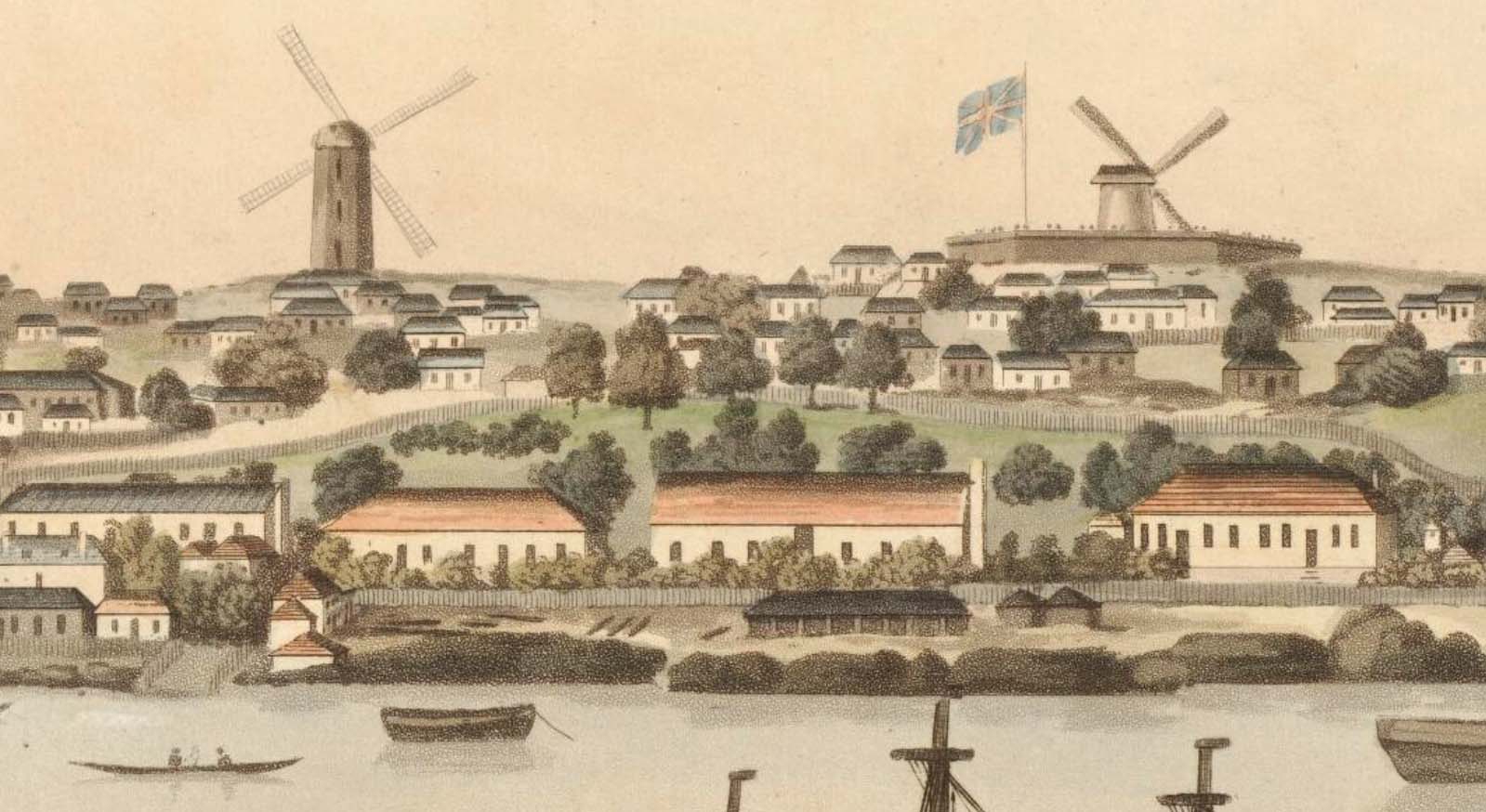

Above, the hexagonal-shaped Fort Phillip (right) was built around Davis' first windmill in 1804–1806. This painting, published in 1810, also shows the wooden smock mill (left) built by Nathaniel Lucas in 1806 – see description below. Detail from New South Wales, view of Sydney from the east side of the cove. No. 2 [picture] by John Heaviside Eyre. National Library of Australia.

NUMBER 8: The storm-wrecked Second Government Windmill

In 1796, another, larger, stone windmill was started near Observatory Hill at Sydney Cove. This became known as the 'Second Government Mill' or the 'Military Mill'. It appears that John Davis was also the millwright for this mill.

Hunter proudly stated that this mill was substantial and well-built, and that it 'will last for two hundred years.' [25] The stone tower was 9m high and its inside diameter was 6m.[26]

Then in June 1799, a disastrous storm struck!

Just as the mill's roof was being built, a huge storm hit Sydney. The stone tower was so badly damaged that they had to demolish it completely, then lay the foundations of the mill once again.[27]

A new, even taller, windmill was built on the ruins, but, according to the next Governor, Philip Gidley King, it was not completed until late 1802.[28] Nevertheless, this windmill, once finally completed, operated until the 1820s.

Above, the Second Government Windmill, or Military Windmill, built near Sydney Cove. Detail from a painting by Major James Taylor in ca. 1821, 'Sydney looking south from Flagstaff Hill', State Library of NSW.

Another severe accident befell a workman on this windmill in 1803. Walter Taylor was struck by one of the windmill vanes as he was repairing it. The blow totally splintered the massive wind vane, but remarkably, Taylor survived! [29]

NUMBER 9: A failure-prone watermill at Parramatta

In 1799, under Governor Hunter, work began on building a large Government watermill on the river at Parramatta.[30] An unnamed man undertook the construction work. However, floods impacted the mill in 1801, making it painfully clear how damaging flooding on the Parramatta River could be to a watermill.[31]

To finally get the mill finished, Governor King brought the skilled millwright, Nathaniel Lucas, and a Master Boat-builder named Alexander Dollis to Sydney from Norfolk Island in 1803.[32] They had to virtually rebuild the mill. Gangs of convicts were used to dig the long mill water race.[33]

This watermill was built from stone and was three stories high. It had a 5.4m diameter overshot waterwheel that was 45cm wide. It operated a single pair of millstones.

In 1804, only one month after the major construction of the mill had concluded, heavy rain set in, and the mill dam was washed way. The dam wall was repaired, but the timber used shrank because it was green. Heavy rain continued to fall, and the dam failed again. A stone dam wall was erected, but it continued to collapse in heavy rain through to 1806! [34]

In 1805, it was reported that the watermill could grind six to eight bushels of wheat per hour.[35] However, ultimately, this watermill failed because, at the site that had been chosen for this mill, its water supply was usually either inadequate, or destructively flooding.[36]

King finally had to admit,

'I am sorry to say that the great labour which has been bestowed in constructing an excellent water-mill and dam at Parramatta will not in any manner recompense the labour that has been bestowed upon it.' [37]

The botanist, George Caley, wrote a sombre postscript to this story. He said that eventually the water-driven mechanism of the Parramatta mill was scrapped, and oxen were used to power the mill. This too failed, and horses were tried in their place. Even the horses could not drive this mill, so at length the whole flour mill was abandoned.[38]

Eventual success despite overwhelming odds

The stories of these first, disaster-prone flour mills in Sydney reveal how complex and challenging it was to construct an efficient watermill or a windmill in an isolated penal colony in the late 1700s.

The reasons for the failure of these mills included the following:

– Unseasoned local Sydney timber was used to make some mechanisms (in England, mill gear wheels were made from well-seasoned, dense timbers such as apple wood) – the Sydney timber dried out and split, and the gear wheels warped, ruining the mechanics of these mills;

– Poor quality mortar was used to build their walls (deposits of lime had not been found near Sydney) – the mill walls failed under the constant vibration and stresses produced by the huge working mechanism; and

– Inexperienced millwrights made errors in designing the gear wheels.

Compounding this, the mill builders endured devastating storms, destructive floods, and tragic accidents.

Nevertheless, the courage, persistence, and ingenuity of these early mill builders are inspiring. From 1800 onwards, many more flour mills – both windmills and watermills – were built in Sydney (see below), benefitting from the hard lessons learned by Sydney's early mill builders. Many of these mills enjoyed lasting success. After immense hard work, the first successful flour mills for the settlement at Sydney Cove were at last established.

WHO WERE SYDNEY'S FIRST MILL BUILDERS? • Master-Miller, Thomas Allen (or Allan) |

Expansion of flour milling in Sydney after 1800

A Government Windmill built by Lucas

When the millwright, Nathaniel Lucas, moved permanently to Sydney from Norfolk Island in 1805, he brought with him the working parts for two windmills. He used one set of parts to build the third Government Windmill at Sydney Cove. It was a smock mill built near Fort Phillip, on today's Observatory Hill. An 1806 newspaper article reported:

'The frame of an octagon smock mill was last week erected by Mr. Nathaniel Lucas, for the use of Government, near the Esplanade of Fort Phillip. The height of the frame is 40 feet, and the diameter of the base, from opposite angles, 22 feet. It is to work two pair of mill-stones, which are the best that could be procured at Norfolk Island ...' [39]

Above left, the smock windmill built by Nathaniel Lucas near Sydney Cove in 1805. This was Sydney's third Government Mill and it used millstones quarried on Norfolk Island. In the background on the right can be seen a windmill tower – the remains of Davis' first Government Windmill (described above), by this stage enclosed inside Fort Phillip . Detail from a painting by Major James Taylor in ca. 1819–1821, 'Parramatta River Sydney Harbour', State Library of NSW.

Sydney's first private windmills

All the mills described so far had been built at Government expense. However, in about 1800, the first commercial windmills began to be built in Sydney.

The first private windmill is associated, in some sources, with the name of a 1794 free settler, John Boston. However, this mill may have actually been established by John Palmer.[40] Palmer had been a Naval Purser on the First Fleet. He was appointed the Commissary B of the colony in 1791.

This small mill was constructed in about 1800 from timber. A bakehouse of stone and brick was also established nearby. These buildings were on the ridge on the eastern side of Sydney Cove, in an area known as the Government Domain, near today's Conservatorium of Music.

Later, in 1805, Nathaniel Lucas also built a private, wooden, post-mill on a lease in the Government Domain, using the second set of components that he had brought to Sydney from Norfolk Island. Then in 1806, John Palmer established another larger stone windmill in the same area.[41]

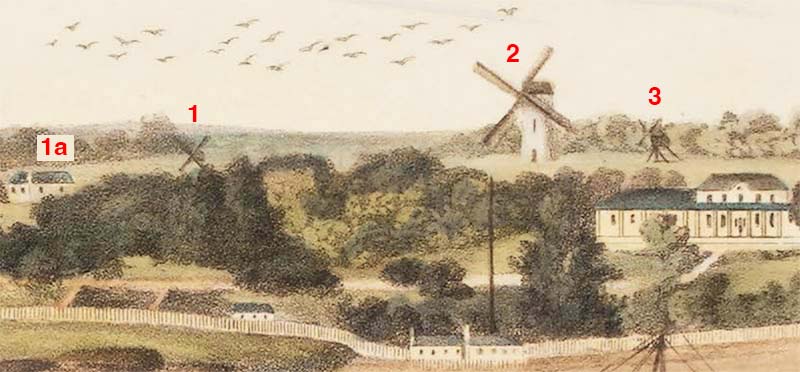

Above, a painting of three windmills in the Government Domain area, near Sydney Cove, in ca. 1809. 1. John Palmer's first windmill; 1a. John Palmer's bakehouse; 2. John Palmer's much larger, stone, second windmill; and 3. Nathaniel Lucas' privately-built wooden post mill. Government House can be seen on the far right. Detail from a watercolour by John Eyre, 'East view of Sydney in New South Wales', State Library of NSW.

B: Commissary. The Commissary was the Government official who managed the colony's stores.

Further growth of milling in Sydney

In the following decades, successful windmills and watermills were established throughout Sydney, at places including Millers Point, Pyrmont, Darlinghurst, Barcom Glen (Paddington), and Parramatta. The first Steam Flour Mill in the colony was also established in 1815 at Cockle Bay.

This rich background of endeavour set the scene for the enterprising Singleton Family, who established more than ten successful flour mills in regional NSW, at Kurrajong, Wisemans Ferry, Singleton, Clarence Town, and Maitland.

What millstones were used in Sydney's first mills?

Pairs of the huge, one-tonne millstones, that were used for grinding flour, were occasionally brought to Sydney Cove in sailing ships, from 1788 to 1810. However, for the early flour mills of Sydney, millstones were scarce.

Unfortunately, the local sandstone and other stone types in the Sydney area were unsuitable for making millstones. Moreover, it was three decades before imported supplies of the French Burr Millstones, much preferred by millers, became readily available in Sydney.

Read about the millstones that were used in Sydney's first large-scale flour mills.

COLONIAL MILLSTONES In desperate need of millstones, settlers in Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia, and Western Australia tried to quarry them locally. |

Can you provide more information We welcome contributions! Please Contact Us. |

REFERENCES

Abbreviations:

HRA – Historical Records of Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-442186184

HRNSW – Historical Records of New South Wales. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-343230396

1. Collins, David (1798) An account of the English Colony of NSW. Volume 1. London; Davey, L, Macpherson, M and Clements, FW (1947) The hungry years : 1788-1792. Historical Studies, 3 (11): 187-208.

2. HRA, 19 March 1792, Series 1, Vol 1, page 339.

3. Selfe, Norman (1902) Some notes on the Sydney windmills. The Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, 1(6): 96-107; Jack RI (1983) Flour mills. In: Industrial Archaeology in Australia, Birmingham J, Jack I and Jeans D (eds). Heinemann Publishers Australia.

4. Selfe, Norman (1902) Some notes on the Sydney windmills. The Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, 1(6): 96-107.

5. Collins, David (1798) An account of the English Colony of NSW. Volume 1. London. – In November 1793, Collins referred to wheat that 'passed through the large mill at Parramatta'.

6. The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 December 1896.

7. Selfe, Norman (1900) Annual address. Delivered to the Engineering Section of the Royal Society of New South Wales. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 34: i-xxix. Archived at Biodiversity Heritage Library.

8. The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 December 1896.

9. Selfe, Norman (1900) Annual address. Delivered to the Engineering Section of the Royal Society of New South Wales. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 34: i-xxix. Archived at Biodiversity Heritage Library.

10. HRA, 1 July 1794, Series 1, Vol 1, page 480.

11. Collins, David (1798) An account of the English Colony of NSW. Volume 1. London.

12. Collins, David (1798) An account of the English Colony of NSW. Volume 1. London; Selfe, Norman (1900) Annual address. Delivered to the Engineering Section of the Royal Society of New South Wales. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 34: i-xxix. Archived at Biodiversity Heritage Library.

13. Ibid.

14. HRNSW, 1 May 1794, Vol 2, page 215.

15. HRNSW, 10 May 1794, Vol 2, page 216.

16. Collins, David (1798) An account of the English Colony of NSW. Volume 1. London.

17. HRA, 25 June 1797, Series 1, Vol 2, page 31.

18. Selfe, Norman (1900) Annual address. Delivered to the Engineering Section of the Royal Society of New South Wales. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 34: i-xxix. Archived at Biodiversity Heritage Library; Collins, David (1802) An account of the English Colony in New South Wales. Volume 2. London.

19. HRA, 1 June 1797, Series 1, Vol 2, page 13.

20. Collins, David (1802) An account of the English Colony in New South Wales. Volume 2. London.

21. Memorial from John Davis to Governor Macquarie, 5 February 1810, Colonial Secretary's Papers, 1788-1856, Fiche 3003, Memorial number 83b. Accessed from Ancestry.com.au Image number 124. https://www.ancestry.com.au/imageviewer/collections/1905/images/32086_228284__0001-00000?usePUB=true&_phsrc=ghk803&pId=161101

22. Collins, David (1802) An account of the English Colony in New South Wales. Volume 2. London.

23. Hall, Barbara (2000) A desperate set of villains. Self-published.

24. HRA, 28 September 1800, Series 1, Vol 2, page 618; Tatrai, Olga (1994) Wind and watermills in old Parramatta. Marrickville, NSW, page 30.

25. HRNSW, 12 November 1796, Series 2, Vol 1, page 675.

26. Collins, David (1802) An account of the English Colony in New South Wales. Volume 2. London.

27. Ibid.

28. Selfe, Norman (1902) Some notes on the Sydney windmills. The Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, 1(6): 96-107.

29. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 17 June 1803.

30. HRNSW, 25 September 1800, Vol 4, page 154.

31. HRA, 1 March 1804, Series 1, Vol 4, page 468.

32. Ibid.

33. Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 6 November 1803.

34. Caley, George (undated) An account of a water-mill errected (sic) at Parramatta in New South Wales. In: Tatrai, Olga (1994) Wind and watermills in old Parramatta. Marrickville, NSW.

35. Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 17 February 1805.

36. Tatrai, Olga (1994) Wind and watermills in old Parramatta. Marrickville, NSW, page 34.

37. HRA, 20 December 1804, Series 1, Vol 5, page 171.

38. Caley, George (undated) A short account relative to the proceedings in New South Wales, from the year 1800 to 1803, with hints and critical remarks. In: Historical Records of NSW, Vol 5, page 294.

39. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 16 February 1806.

40. Casey & Lowe Associates (2002) Archaeological investigation, Conservatorium site, Macquarie Street, Sydney. Vol 1: History & archaeology. Chapter 2: Historical Context., and Vol 2: Response to research design. Chapter 14: The Bakehouse and Mill.

41. Ibid.

Read More About Sydney's Early Flour Milling History

•• Sydney's First Mill Builders •• Sydney's First Millstones •• Australia's Colonial Millstones ••

Read More About Norfolk Island's Flour Milling History

•• Overview •• First Settlement Flour Mills •• Second Settlement Flour Mills •• Nathaniel Lucas •• Robert Nash •• Norfolk Island Millstones ••