Flour Mills of the First Norfolk Island Settlement:

1788 to 1814

Topics: First Settlement Flour Mills, Querns, Millstones, Watermills, Windmills

Singleton Mills homepage > Norfolk Island Flour Milling Overview > First Settlement Flour Mills

The beginning of the First Settlement

Lieutenant Philip Gidley King established an outpost British Settlement on Norfolk Island on 6 March 1788.

Above, the First Settlement on Norfolk Island. Notice the jagged reef of limestone in the foreground (along the ocean's edge) which made shipping access to the settlement extremely dangerous. However, it was later found that this limestone was useful for quarrying millstones for the island's flour mills. This ca. 1805 watercolour by John Eyre was adapted from an engraving by W. Lowry that was published in Collins D (1798) An account of an English colony in New South Wales. The date of the original drawing must therefore have been earlier than 1798.

By 1790, the parent penal colony back at Sydney Cove, New South Wales (NSW), Australia, was on the brink of starvation because their crops had failed and expected supply ships did not arrive. Governor Arthur Phillip hoped that the fertile soil of their colony on Norfolk Island might better feed the settlers. So, month by month, he sent more transport ships with new dispatches of convicts and guards from Sydney to add to the population on Norfolk Island. By May 1792, the Norfolk Island population had peaked at 1156 people.

King was the Commandant of the Norfolk Island settlement for seven of its earliest years (1788-1790 and 1791-1800). His detailed letters and diaries provide valuable accounts of the life of the early settlers, with their many hardships and achievements.

The need for flour mills

Casks of flour and bread had been sent to Norfolk Island for the settlers. However, some of these precious supplies were lost, being damaged by water, or destroyed by abundant pests such as weevils and Polynesian rats.

For example, Lieutenant King wrote in his diary in August 1788,

'Opened a Cask of Beef & one of Flour, the latter of which had a large Rats nest in it & several dead young ones. This Cask came by the Supply & wanted 50 lbs of the weight.' [1]

… and in 1789,

'in getting up the Ground two of Flour Cask from under the Surgeons house found a Great Quantity of Water had lodged during the yrs rains. On Opening the Cask found the Flour in them very much damaged, As Many of the Casks were like dough, Cannot ascertain the Quantity lost till the whole 36 Casks which were in Ground Store are opened.' [2]

As first expected, crops of wheat and maize did grow well on Norfolk Island. The issue was, though, to manage to grind this wheat into flour before it was destroyed by vermin.

King wrote in 1788,

'The Rats have destroyed every grain of Wheat & barly which were coming up, & ye Grubs have destroyed all the potatoes & other vegatables which were also coming up, except the Yams which they have damaged… To destroy the Grubs I have try’d Ashes… but all without Effect they are so numerous that it is impossible to thin them by picking them off.'[3]

Using hand-mills to grind wheat

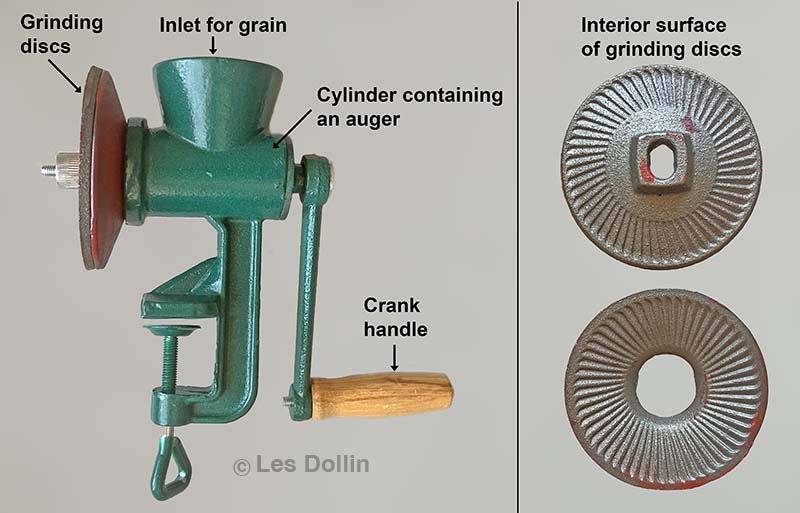

1. Iron hand-mills

An iron hand-mill could grind, at best, a quarter of a bushel A per hour

Thirteen iron (or steel) hand-mills had been brought to Norfolk Island to grind flour. However, with a population of around 1000 people, these iron mills, unsurprisingly, soon wore out.

Above, this modern replica of a simple steel hand-mill for grinding grain provides an idea of the possible design of Norfolk Island's first hand mills. We have not found any images of the original hand-mills that were used in Australia and Norfolk Island in the early 1800s, although hundreds must have been imported or produced in Sydney. We would be interested to hear from any reader who can provide such an image – please help us continue to expand the information about Australia's first flour milling enterprises on this website!

A man who had been a convict in NSW in 1838 recalled that a steel hand mill in good condition could have ground about a quarter of a bushel of wheat in one hour. However, an old rusty hand mill took six hours to grind that same amount.[4]

A: Bushel. One imperial bushel of wheat weighs about 25 kg.

2. Stone Querns

Alternatively, it was possible to cut certain types of stone into small primitive hand-mills. These were called 'Querns' and, in various forms, these had been used for milling grain across the world for thousands of years. These were more durable than steel hand-mills, and as it was discovered, they could be produced on Norfolk Island:

Large deposits of a Limestone called Calcarenite had been discovered along the southern beaches of Norfolk Island – as shown in the first painting on this webpage. An attempt was made to cut both querns and full-sized millstones from this material.

Above left, a woman in India holds the handle of a pair of small quern stones used for grinding grain by hand. Above right, a man positions a full-sized millstone, whilst standing on the second millstone of the pair – millstones like this were the type used in large-scale, powered flour mills. Both images are from Wikimedia Commons: left, by Ramesh Lalwani; right, by Rasbak.

King wrote in 1794,

'The great distress which every Person Experienced for want of means to manufacture their Grain into Flour (As the hand mills are entirely useless) induced the only Stone Mason there is on the Island to make a Pair of Quearns from some Stones found on the Beach.' [5]

The Calcarenite querns proved to be very effective, and King ordered many more to be cut and supplied to local families, so that they could grind their wheat rations.

Eight months later, King wrote,

'The inconvenience attending the Labourer & others not being able to Grind their Ration of Grain is now done away, as there are very few who have not a Pair of Querns in their Houses, exclusive of those which are kept in a Mill-house for the Publick use.' [6]

Nevertheless, the chore of grinding the hard wheat grains into flour with these little mills was time consuming and arduous. There was an urgent need to establish large-scale flour mills on Norfolk Island. Treadmills powered by convicts could be a solution, but King hoped that a watermill or a windmill could be set up on the island.

Quarrying full-sized millstones on Norfolk Island

The stone mason found that efficient millstones could also be cut from the Limestone deposits on Norfolk Island. These Norfolk Island Calcarenite Limestone millstones were used in all the full-scale flour mills that were used during the First Settlement.

Calcarenite Limestone Millstones

|

Nathaniel Lucas and Norfolk Island's first flour mills

Amongst the convicts in on Norfolk Island, King discovered an industrious man with carpentry and milling skills. His name was Nathaniel Lucas. King appointed him as Master Carpenter and set him the task of building large-scale flour mills for the colony.

Read more about the life story of Nathaniel Lucas and his wife, Olivia Gascoigne

When he first arrived on the island, Lucas mostly had general carpentry skills. However, he developed his millwrighting skills over the years on Norfolk Island and succeeded in building a number of effective flour mills.

King wrote in 1795,

'I have the pleasure to observe that a Millwright is not wanted, as Nath.l. Lucas … has some time back finished an Overshot Water Mill, which will Grind & Boult B Sixteen Bushels of Wheat daily, which is more than sufficient to supply the Store with the Weekly Expense of Flour, He is now erecting a Wind Mill for himself, which is nearly finished.' [7]

B: Boult (usual spelling: 'Bolt'). The machine that purifies or bolts the flour is called a 'Bolter'. It removes the bran from the flour by beating the flour through a tube of fine cloth.

Large-scale flour mills built during the First Settlement

In 1794, a series of attempts began to build larger-scale flour mills in Arthur's Vale on Norfolk Island. This flat, open valley, just northwest of the main settlement, was named in honour of Governor Phillip.

From the diaries and letters of King, it appears that four mills were built in Arthurs Vale, each probably incorporating materials from the earlier ones. In addition, two windmills were built in 1795. Nathaniel Lucas was involved in constructing many of these mills, and the millstones were quarried from the Calcarenite Limestone.

1. A Six-man Mill – April 1794

2. A Two-man Mill – June 1794

3. A Small Overshot Watermill -- 1795

4. A Larger Overshot Watermill – 1795

5. Two Windmills – 1795

1. A Six-man Mill – April 1794

Six men could only grind half a bushel per hour

King wrote,

'Those Quearns succeeded so well, that I caused the Overseer of the Carpenters [Nathaniel Lucas] to attempt the construction of a Horse or hand Mill'. [8]

The mill was begun on 12 March 1794 and completed on 12 April 1794.

Unfortunately, when the mill was tried out, King considered it a failure, because it required too much manpower to run. The Calcarenite millstones, however, were considered to be very good and were stored for the next attempt.

King wrote,

'… although the Man did his best, yet it required too great power to work it.

If a Mill wright could be sent here to give instruction, any number of overshot Mills might be Erected on the Island which abounds with several natural situations for Works of that kind, as there are a sufficient Quantity of Mill & Quearn Stones for every present & future occasion.' [9]

2. A Two-man Mill – June 1794

Two men could grind one bushel per hour

After the failure of the first mill, two men each undertook to redesign and build a mill, based on 'the principles of a wind or watermill', but operated by winches.

King wrote:

'A Carpenter and a Blacksmith have each begun a Mill on the Principles of a Water Mill, excepting that it is to turn by Winches, and is to be worked by two Men instead of the Bucket Wheel,

if either of these Succeed, it will be an inducement to attempt the Construction of an Overshot Mill, as there are many favourable Situations for a Work of that Kind.' [10]

One of these mills did succeed!

King wrote,

'One of the Mills was finished on the 27th [June 1794]. It is I believe as perfect as Anything of the kind can be, that is not worked by Wind or Water,

And is in every Respect conformable to the Construction of an Overshot Mill, except that it Works by a Winch and Flywheel, and requires two Men to Work it, who find it hard work to Grind One Bushel of Wheat in an Hour,

Soon after the Seed Time is over, I mean to attempt the Construction of a Water or Overshot Mill.' [11]

3. and 4. Two Overshot Watermills – 1795

Could grind up to 20 bushels of wheat daily

A small weatherboard watermill with an overshot wheel was constructed during 1795 in Arthur's Vale, driven by water from Watermill Creek. Soon afterwards, it appears to have been enlarged – King stated that a 'larger one with a boulter' was completed.[12]

King wrote in two different documents in July 1795,

'… Nath.l. Lucas… has some time back finished an Overshot Water Mill, which will Grind & Boult Sixteen Bushels of Wheat daily, which is more than sufficient to supply the Store with the Weekly Expense of Flour,'

'The Water Mill, which is perfect in its Structure, is of the utmost Advantage to the Inhabitants…' [13]

Windmill Creek, which flowed through the valley, had been recognised, since the early years of settlement, to be large enough to power a watermill.[14] A mill dam was constructed across the stream and a watermill was built. Mill races were cut, leading to the mill waterwheel, and then back to the stream.

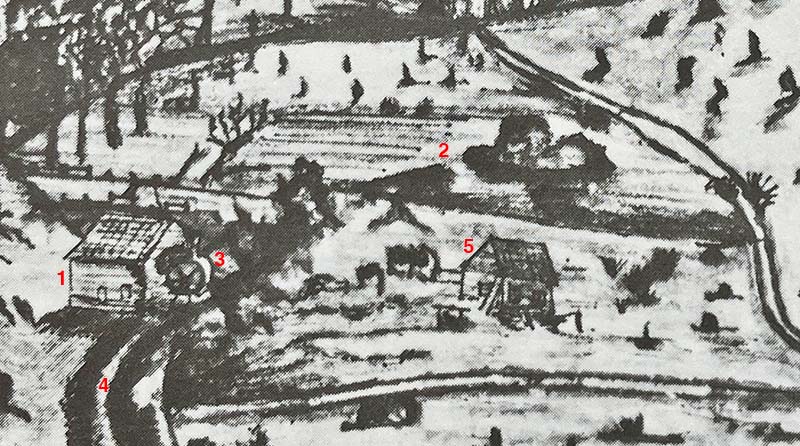

Above, a drawing of the wooden First Settlement Watermill (1) in Arthur's Vale in 1796. Water from the mill dam (2) would have been channelled to the mill through a head race. After powering the waterwheel (3), the water would have been carried back to Watermill Creek through a tail race (4). The other building (5) may have been a mill house for the miller. Detail from: 'View of the Water Mill in Arthur's Vale, Norfolk Island', by William Neate Chapman. State Library of NSW.

A team of 40 men, supervised by Nathaniel Lucas, worked for three months to construct this mill. Apparently this mill was constructed for the cost of three ewe sheep! [15]

In 1796, the wall of the mill dam was raised to increase the power of the watermill. King wrote,

'From a late addition of 3 feet to the height of the dam it will now grind 20 bushels of wheat daily, which has done away the great inconvenience of every man being obliged to grind his ration before it can be dressed.' [16]

5. Two Windmills – 1795

In July 1795, Nathaniel Lucas was recorded to have nearly finished building a windmill for himself.[17]

Then in October 1796, King reported that two well-furnished windmills had been erected by settlers and that they were successful.[18]

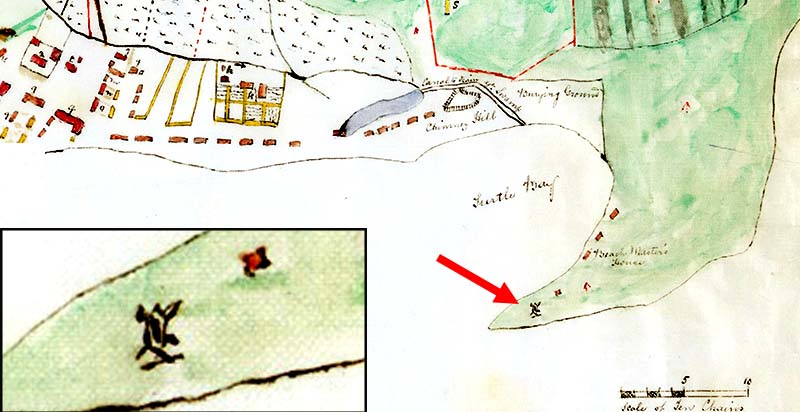

One of the windmills was a postmill C constructed on an area of flat open land at Point Hunter on the south eastern coast of Norfolk Island, and Nathaniel Lucas also built a windmill 'on his own estate'.

Above, a postmill-style windmill (arrow) that was built on Point Hunter during the First Settlement of Norfolk Island, as seen in a plan of the island, ca. 1794. A magnified view of the postmill is shown in the inset. Detail from 'Plan of the town of Sydney on the south side of Norfolk Island with the adjacent grounds' by William Neate Chapman. State Library of NSW.

C: Postmill. A postmill is a type of windmill, with a small wooden building containing the mill machinery. Windmill vanes are attached to one wall of this building. The building is mounted on a sturdy timber post, which is supported by sloping buttress posts. The whole building can be rotated, so that the windmill vanes face directly into the wind to produce the maximum power.

Finding suitable timber

Another challenge for the First Settlement mill builders was identifying suitable local timber for making the mill cog wheels, the waterwheel and other components. In England, hundreds of years of experimentation had shown that well-seasoned, dense timbers, such as apple wood, were the best for flour mill woodwork.

Above, some of the massive and complex wooden gear work inside the Steenmeulen windmill in France. Photograph by Anne Dollin.

With the abundance of Norfolk Island Pine Trees on the island, this timber was probably used for much of the woodwork on the mills, at least initially. It was better than the local timber available in Sydney, NSW, and quantities of sawn pine planks were shipped to Sydney for construction work there.[19]

However, over time, it became clear that Norfolk Island Pine timber was not durable in outdoor locations. For instance, fences made from this timber decayed within three years.

Alexander Maconochie, a Superintendent of the Second Settlement, said that timber from the local 'Iron-wood' D tree was used for making mill-cogs and spokes of wheels.[20]

D: Iron-wood. Maconochie identified this tree as the species, 'Notelaea Longifolia'. However, the tree he was describing may actually have been the species, Nestegis apetala.

Nathaniel Lucas moved to Sydney, NSW

In 1796, Norfolk Island's first Commandant, Philip Gidley King, completed his posting there and was replaced by other Commandants. Then in 1800, King was appointed as Governor of NSW, based in Sydney, NSW.

When Governor King took up his post in Sydney, he was dismayed to see the lack of progress that had been made there in constructing flour mills. In contrast, King had been very impressed by the millwrighting work that Nathaniel Lucas had done on Norfolk Island.

So, he invited Lucas to move to Sydney with his family, rather than going to Tasmania with the other Norfolk Island colonists as the settlement closed. King was optimistic that Lucas, with his skills and industrious work ethic, would quickly solve the lack of flour mills in Sydney.[21]

Lucas was to bring to Sydney with him several pairs of the Norfolk Island millstones, along with the workings of a windmill to be erected for the Government. King also permitted Lucas to bring the workings of a second windmill which Lucas could erect for himself in Sydney.[22] Lucas, with his family and all these milling materials, left Norfolk Island in 1805.

Norfolk Island mills after 1805

The British Government had decided in the early 1800s to close the settlement on Norfolk Island. However, many settlers were very reluctant to leave, and the last settlers were not evacuated until 1814. So, operational flour mills were still needed for almost a decade after Nathaniel Lucas and his family went to Sydney, NSW.

One of the remaining settlers who became involved in flour milling after Lucas left was Robert Nash. He had been employed on the island as the Master Boat-Builder.

Nash had completed his own flour watermill on Norfolk Island not long before he was finally forced to accept being evacuated to Tasmania in 1814.

Final closure of the First Settlement

The last people were evacuated from Norfolk Island in 1814. They included a party of convicts whose task was to destroy all the First Settlement buildings. This was done to discourage anyone else from occupying the island.[23]

The First Settlement watermill and windmill buildings were destroyed. However, the mill dam and the water races of the watermill survived, and these were reused during the Second Settlement.

REFERENCES

Abbreviations:

CO – Colonial Office Records 1774-1951.

HRA – Historical Records of Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-442186184

HRNSW – Historical Records of New South Wales. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-343230396

1. Fidlon, PG and Ryan, RJ (1980) The Journal of Philip Gidley King: Lieutenant, R.N. 1787–1790. Australian Documents Library, Sydney, page 94.

2. Ibid, page 132.

3. Ibid, page 53.

4. Jack RI (1983) Flour mills. In: Industrial Archaeology in Australia, Birmingham J, Jack I and Jeans D (eds). Heinemann Publishers Australia.

5. Journal of Philip Gidley King while Lieutenant-Governor of Norfolk Island and Letter to Mrs Gov. King, 1791-1796, Trove: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-26005434/view?partld=nla.obj-26038525, Image 146.

6. CO, 201.10, pages 264. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-914011294/view

7. CO, 201.18, page 28.

8. CO, 201.10, page 264.

9. Ibid.

10. Journal of Philip Gidley King while Lieutenant-Governor of Norfolk Island and Letter to Mrs Gov. King, 1791-1796, Trove: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-26005434/view?partld=nla.obj-26038525, Image 148.

11. Ibid, Image 155.

12. CO, 201.18, page 175.

13. CO, 201.18, page 36.

14. HRNSW, Vol 1, page 186.

15. Collins, D (1798) An account of the English Colony of NSW. Volume 1.

16. HRNSW, Vol 3, page 160.

17. CO, 201.18, page 28.

18. HRNSW, Vol 3, page 160.

19. Fidlon, PG and Ryan, RJ (1980) The Journal of Philip Gidley King: Lieutenant, R.N. 1787–1790. Australian Documents Library, Sydney.

20. Backhouse, J (1843) A narrative of a visit to the Australian colonies. Hamilton, Adams and Co, York.; Maconochie, A (1845) Criminal Statistics and Movement of Bond Population of Norfolk Island, to December 1843. Journal of the Statistical Society of London, 8: 1-49.

21. HRNSW, Vol 5, page 597.

22. HRA, Series 1, Vol 5, page 221.

23. Nobbs, Raymond (1988) Viewing the first settlement. In: Nobbs, Raymond (ed) Norfolk Island and its first settlement 1788-1814. Library of Australian History.

Read More About Norfolk Island's Flour Mills

•• Overview •• First Settlement Flour Mills •• Second Settlement Flour Mills •• Nathaniel Lucas •• Robert Nash •• Norfolk Island Millstones ••